Merge Sort and Recurrence Forms

Week 4, Monday

January 26, 2026

Announcements

- EX1 this week

- PA1 released, due Feb 7, 23:59.

- Lab 3 meets in-person

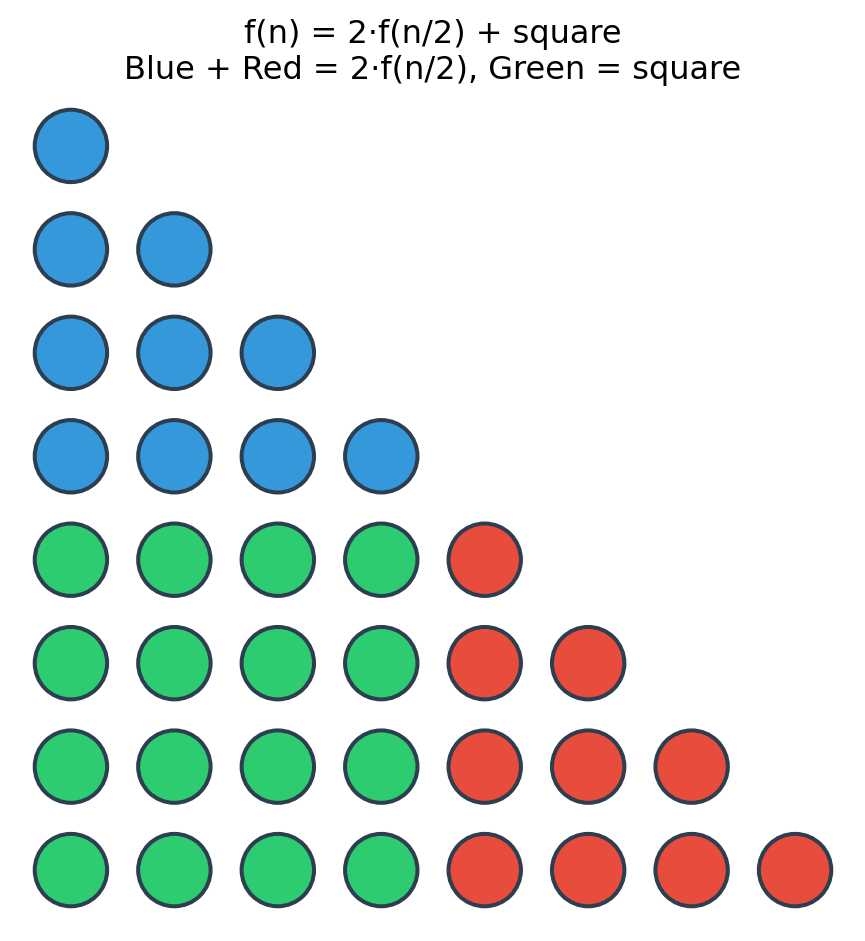

Remember the Triangle?

Last Week’s Recursion

We computed \(1 + 2 + 3 + \ldots + n\) recursively:

The mathematical decomposition: \(f(n) = 2 \cdot f(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor) + (n - \lfloor n/2 \rfloor)^2\)

Two Ways to Compute This

Both compute the same answer. But are they equally fast?

The Critical Distinction

| Code | How many recursive calls? |

|---|---|

2 * triangle_fast(half) |

ONE call, multiply result by 2 |

triangle_double(half) + triangle_double(half) |

TWO calls! |

The mathematical relationship is: \(f(n) = 2 \cdot f(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor) + (n - \lfloor n/2 \rfloor)^2\)

But the time to compute depends on how many recursive calls we make!

Today’s Question

When we write recursive code, how do we figure out its running time?

The answer: We write a recurrence relation for \(T(n)\), the time.

triangle_fast: \(T(n) = T(n/2) + O(1)\) — ONE calltriangle_double: \(T(n) = 2T(n/2) + O(1)\) — TWO calls

Different recurrences → different running times!

Let’s explore this through another recursive puzzle…

A Recursive Puzzle

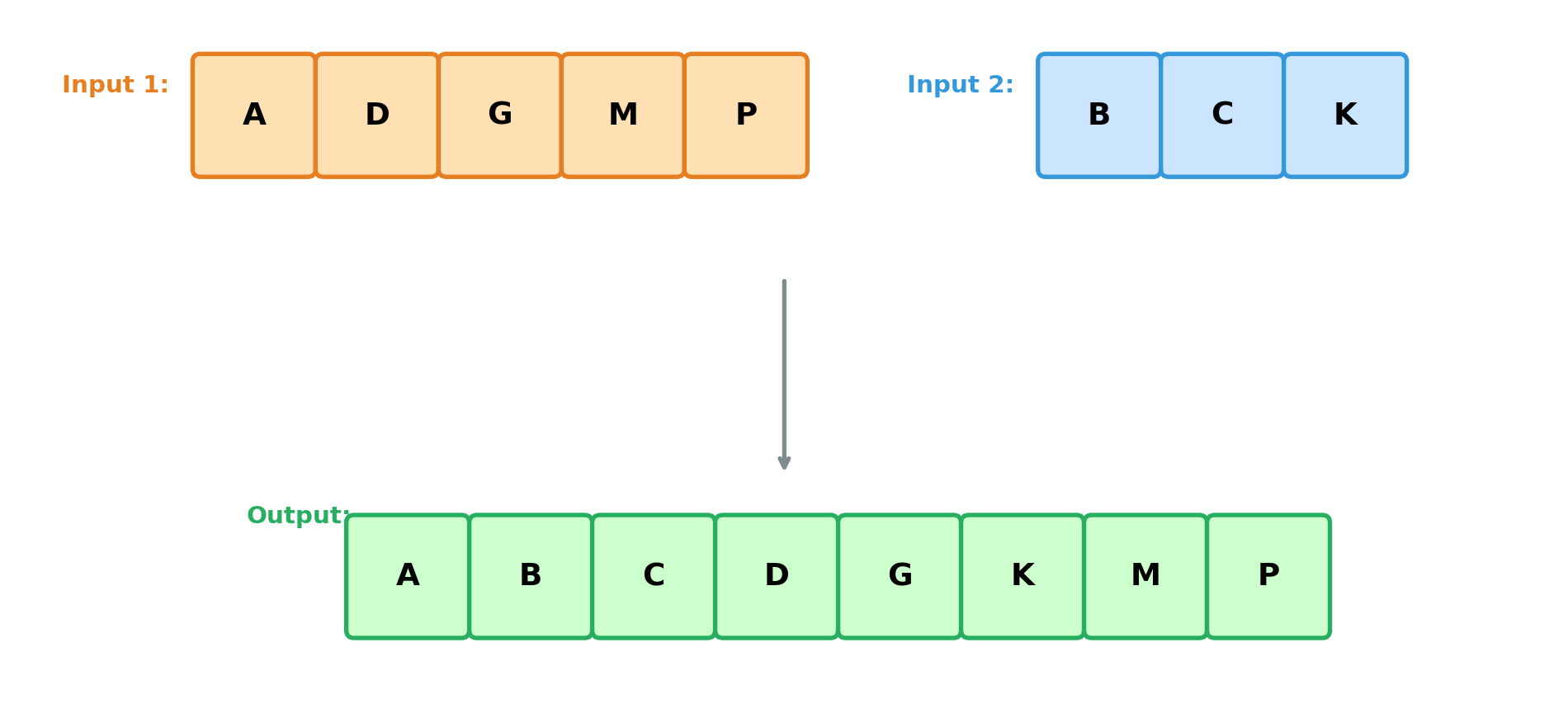

What Does This Function Do?

The Observations

Both inputs are sorted

The output contains all elements from both inputs

The output is sorted

The function: Given two sorted lists, produce one sorted list with all elements.

Let’s Think About It

What’s the simplest case?

What if both lists have elements?

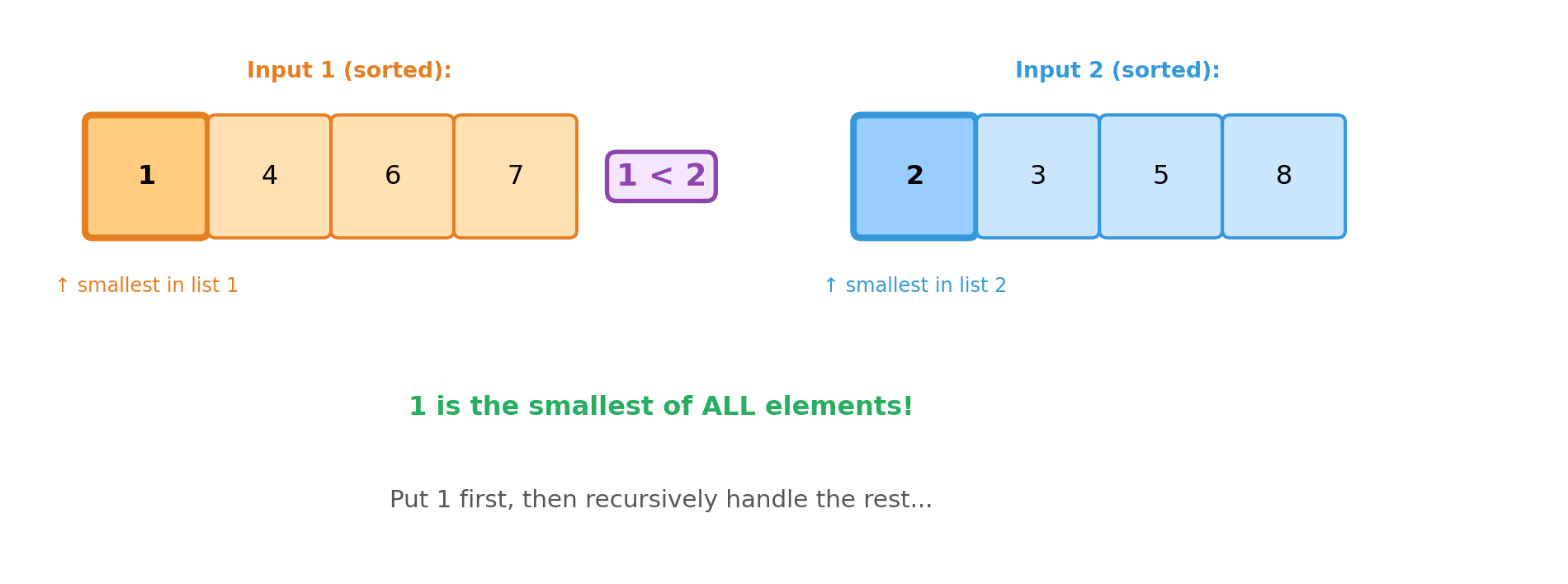

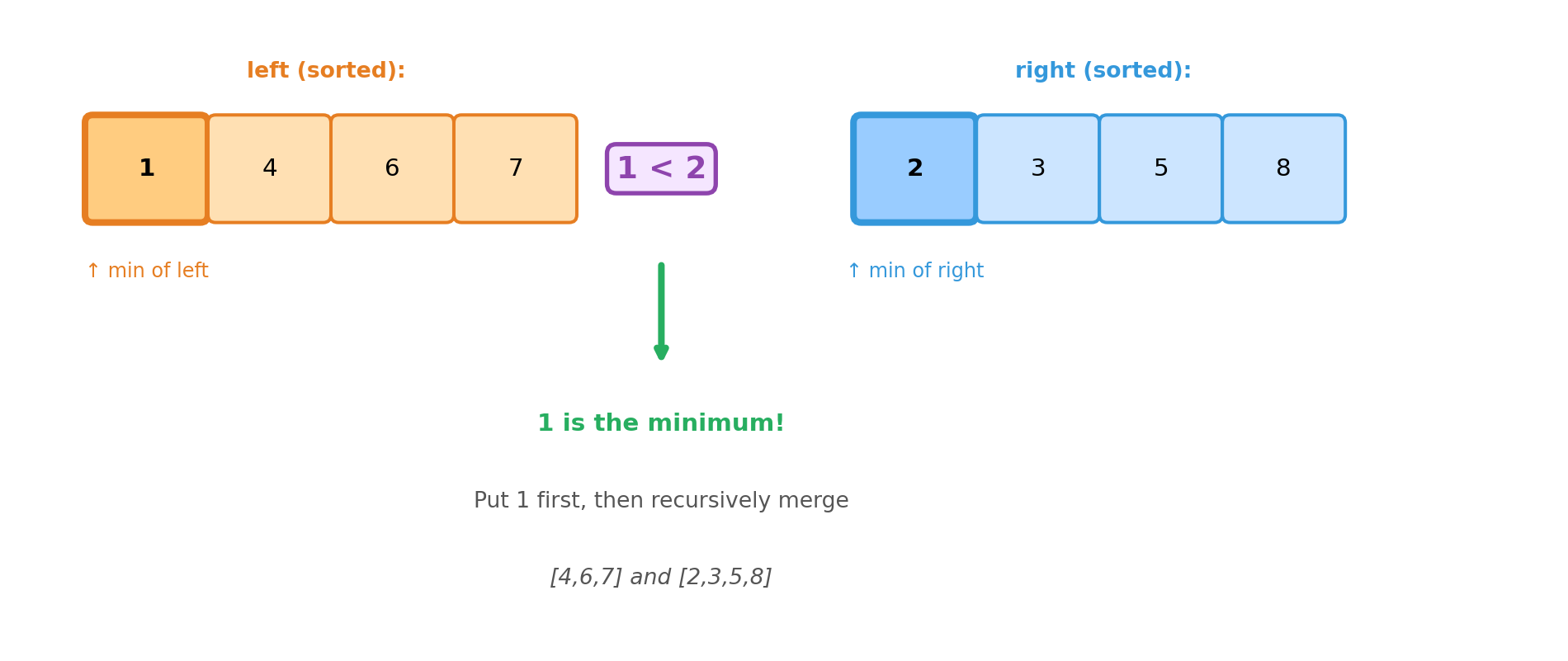

The Key Insight

The smallest element overall must be at the front of one of the lists!

Live Code: Merge

Test It!

Merge Running Time

Each recursive call: processes one element.

How many calls? Exactly \(n\) (total elements).

Running time: \(O(n)\)

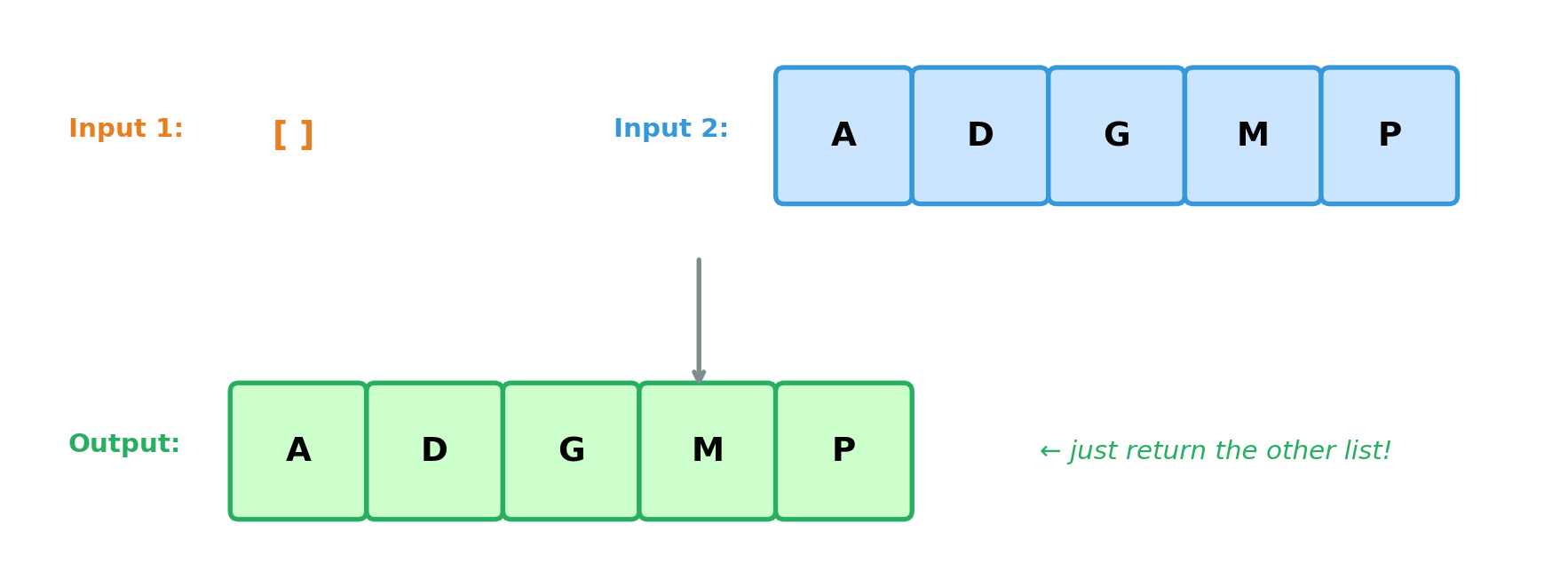

Why is Merge Correct?

Induction on the total size \(n = |left| + |right|\).

Base cases: If either list is empty, return the other. ✓

Inductive step: Assume merge works for total size \(< n\).

Merge Correctness: The Key Insight

Merge Correctness: Proof

Inductive step: Given sorted lists left and right with total size \(n\):

- Compare

left[0]andright[0](the two minima) - The smaller one is the minimum of all elements

- Put it first, then recursively merge the rest (size \(n-1\))

- By IH, the recursive call returns a sorted list

- Prepending the min keeps it sorted ✓

Therefore, merge is correct for all inputs. ∎

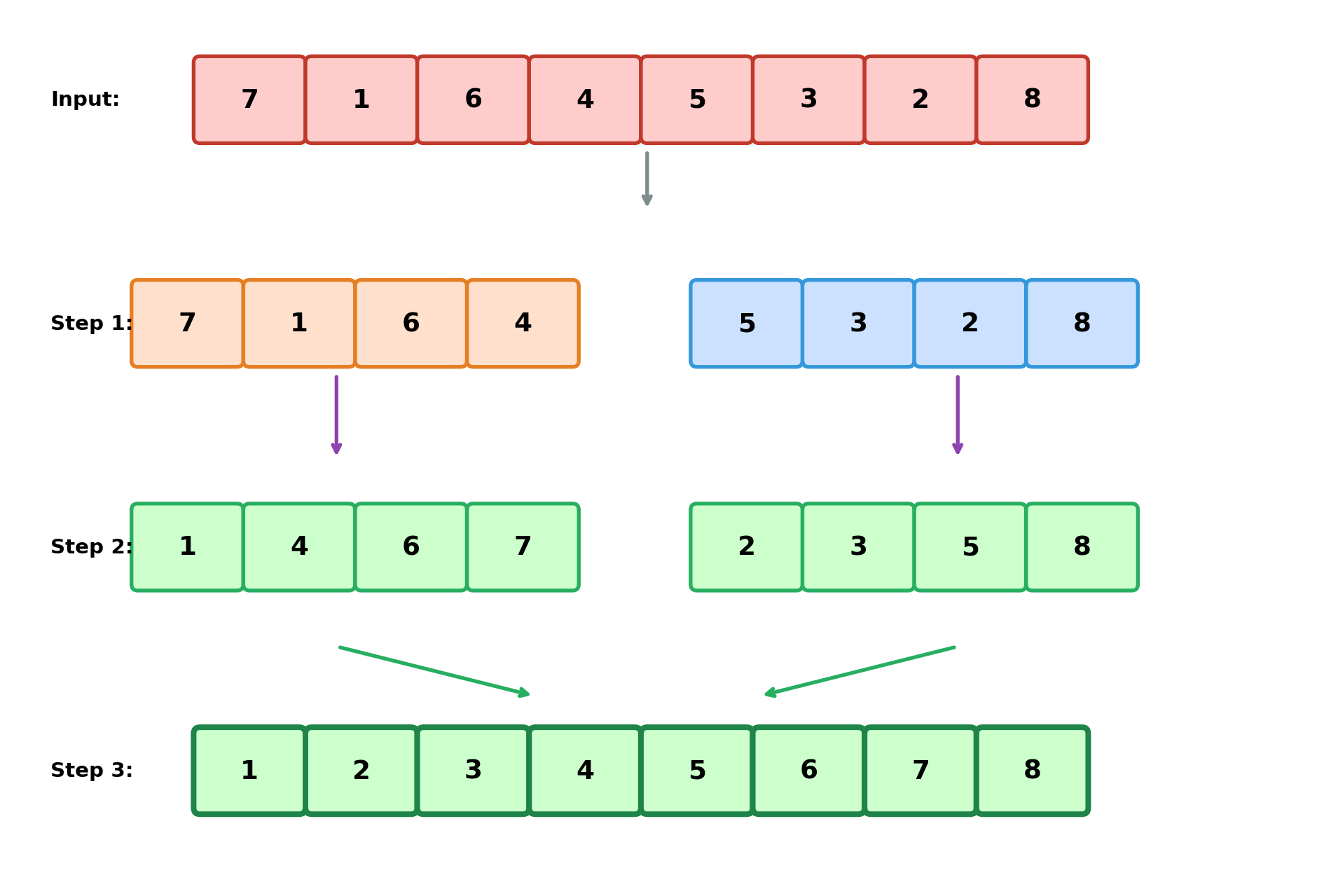

Merge Sort

OK, Now Sort This Array

Putting It Together

Does It Work?

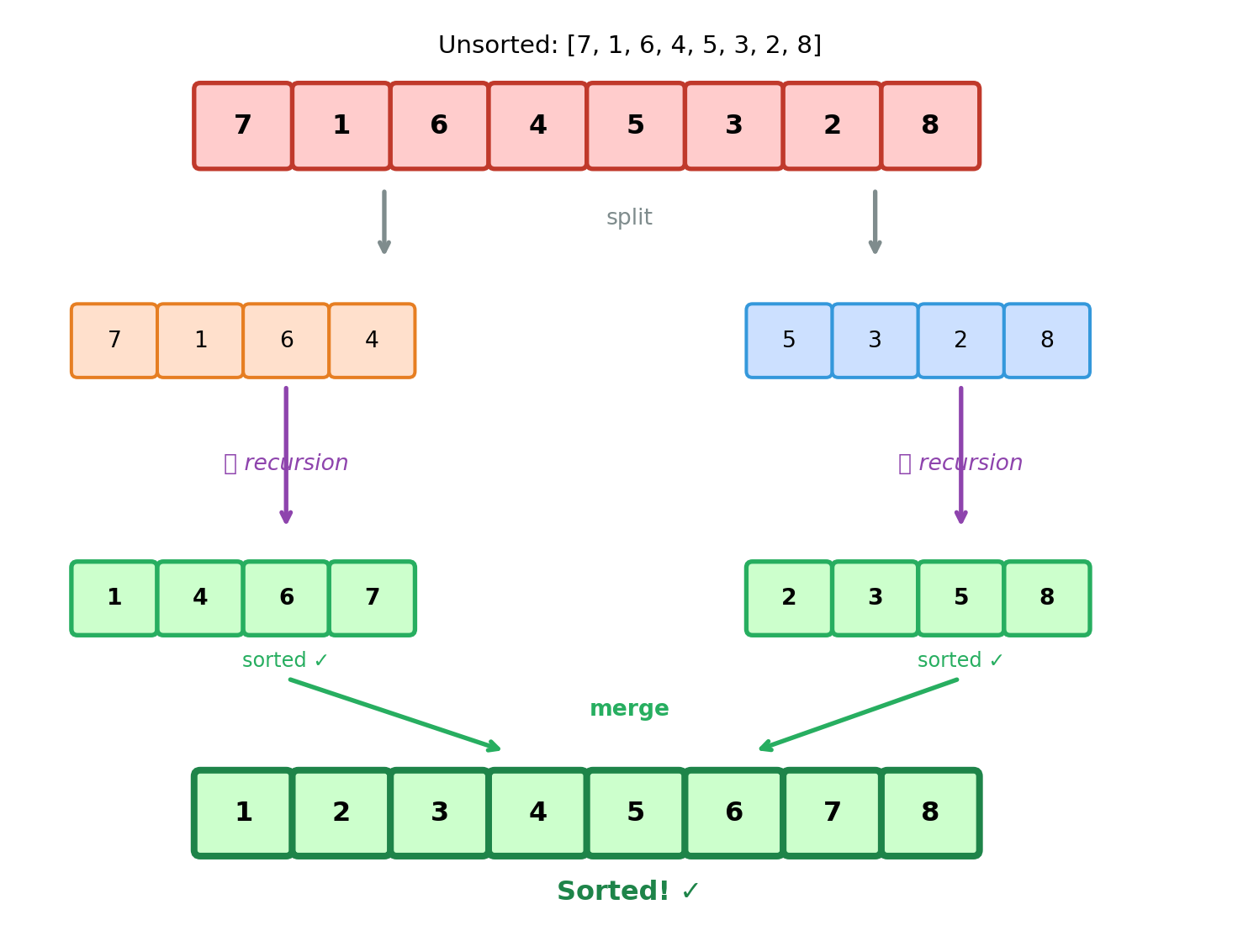

Why Does It Work?

Proving Correctness

Testing shows it works on examples. But how do we prove it always works?

Induction on the size of the input:

- Base case: Lists of size 0 or 1

- Inductive step: If it works for smaller lists, it works for size \(n\)

The Induction Visualized

The Base Case

A list with 0 or 1 elements is already sorted. ✓

The Inductive Step

Assume: merge_sort correctly sorts any list of size \(< n\).

Goal: Show merge_sort correctly sorts a list of size \(n\).

By our assumption, left_sorted and right_sorted are correctly sorted.

Thus they are valid inputs to merge.

We have already proved correctness of merge, so we are done!

Putting It Together

- Base case: ✓ (trivially sorted)

- Inductive hypothesis:

merge_sortworks for sizes \(< n\) left_sortedis sorted (by IH, since size \(< n\))right_sortedis sorted (by IH, since size \(< n\))mergecombines them correctly (by earlier proof)- Therefore

merge_sortworks for size \(n\) ✓

By induction, merge_sort is correct for all \(n\). ∎