Introduction to Recursion

Week 3, Wednesday

January 22, 2026

The 96 Days of DSCI 221

🎵 On the ninety-sixth day…

96 moments of zen 🎵 95 grateful neurons 🎵 94 clever insights 🎵 93 aha moments 🎵 92 merge conflicts 🎵 91 Stack Overflow tabs 🎵 90 refactored functions 🎵 89 git commits 🎵 88 test cases 🎵 87 rubber ducks 🎵 86 coffee refills 🎵 85 keyboard clicks 🎵 84 documentation pages 🎵 83 variable names 🎵 82 edge cases 🎵 81 print statements 🎵 80 whiteboard markers 🎵 79 Piazza posts 🎵 78 recursive calls 🎵 77 helper functions 🎵 76 code reviews 🎵 75 unit tests 🎵 74 bug fixes 🎵 73 loop iterations 🎵 72 hash collisions 🎵 71 array indices 🎵 70 base cases 🎵 69 pointer errors 🎵 68 syntax errors 🎵 67 runtime exceptions 🎵 66 stack frames 🎵 65 heap allocations 🎵 64 binary digits 🎵 63 terminal commands 🎵 62 Slack messages 🎵 61 Discord pings 🎵 60 Zoom breakouts 🎵 59 office hours 🎵 58 study sessions 🎵 57 flashcards 🎵 56 practice problems 🎵 55 lecture notes 🎵 54 code snippets 🎵 53 TODO comments 🎵 52 FIXME tags 🎵 51 deprecation warnings 🎵 50 linter errors 🎵 49 type hints 🎵 48 docstrings 🎵 47 assert statements 🎵 46 boundary checks 🎵 45 null pointers 🎵 44 empty lists 🎵 43 off-by-ones 🎵 42 infinite loops 🎵 41 segfaults 🎵 40 memory leaks 🎵 39 cache misses 🎵 38 race conditions 🎵 37 deadlocks 🎵 36 timeouts 🎵 35 snack breaks 🎵 34 memes shared 🎵 33 playlists made 🎵 32 naps attempted 🎵 31 alarms snoozed 🎵 30 tabs still open 🎵 29 unread emails 🎵 28 doodles drawn 🎵 27 songs on repeat 🎵 26 empty notebooks 🎵 25 highlighters 🎵 24 sticky notes 🎵 23 “almost dones” 🎵 22 existential crises 🎵 21 snacks consumed 🎵 20 walks taken 🎵 19 deep breaths 🎵 18 pokemons 🎵 17 demos 🎵 16 pull requests 🎵 15 code comments 🎵 14 merge commits 🎵 13 Piazza posts 🎵 12 cups of ramen 🎵 11 syntax errors 🎵 10 ChatGPT tabs 🎵 9 hours of sleep 🎵 8 TA office hours 🎵 7 Pomodoros 🎵 6 study rooms 🎵 5 passing tests 🎵 4 stretch breaks 🎵 3 docs read 🎵 2 good friends 🎵 And a latte from Loafe.

The Question

How many treats will you receive on the 96th day (Apr 10)?

\[1 + 2 + 3 + \ldots + 96 = \sum_{k=1}^{96} k = \text{ ?}\]

Proving the Closed Form

Claim: \(f(n) = \frac{n(n+1)}{2}\) where \(f(n) = \sum_{k=1}^{n} k\)

Proof: Consider an arbitrary \(n >= 0\). Then we have the following cases:

Case 1, \(n = 0\) (base case): \(f(0) = 0 = \frac{0 \cdot 1}{2}\) ✓

Case 2, \(n>0\) (inductive case):

Assume for any \(0 < j < n\), \(f(j) = \frac{j(j+1)}{2}\) (Inductive Hypothesis)

\(f(n) = f(n-1) + n\) by definition.

\(f(n-1) = \frac{(n-1)(n)}{2}\) by IH, since \(n-1 < n\).

\(f(n) = \frac{(n-1)(n)}{2} + n = \frac{(n)(n+1)}{2}\) by algebra. ✓

Recursive Thinking

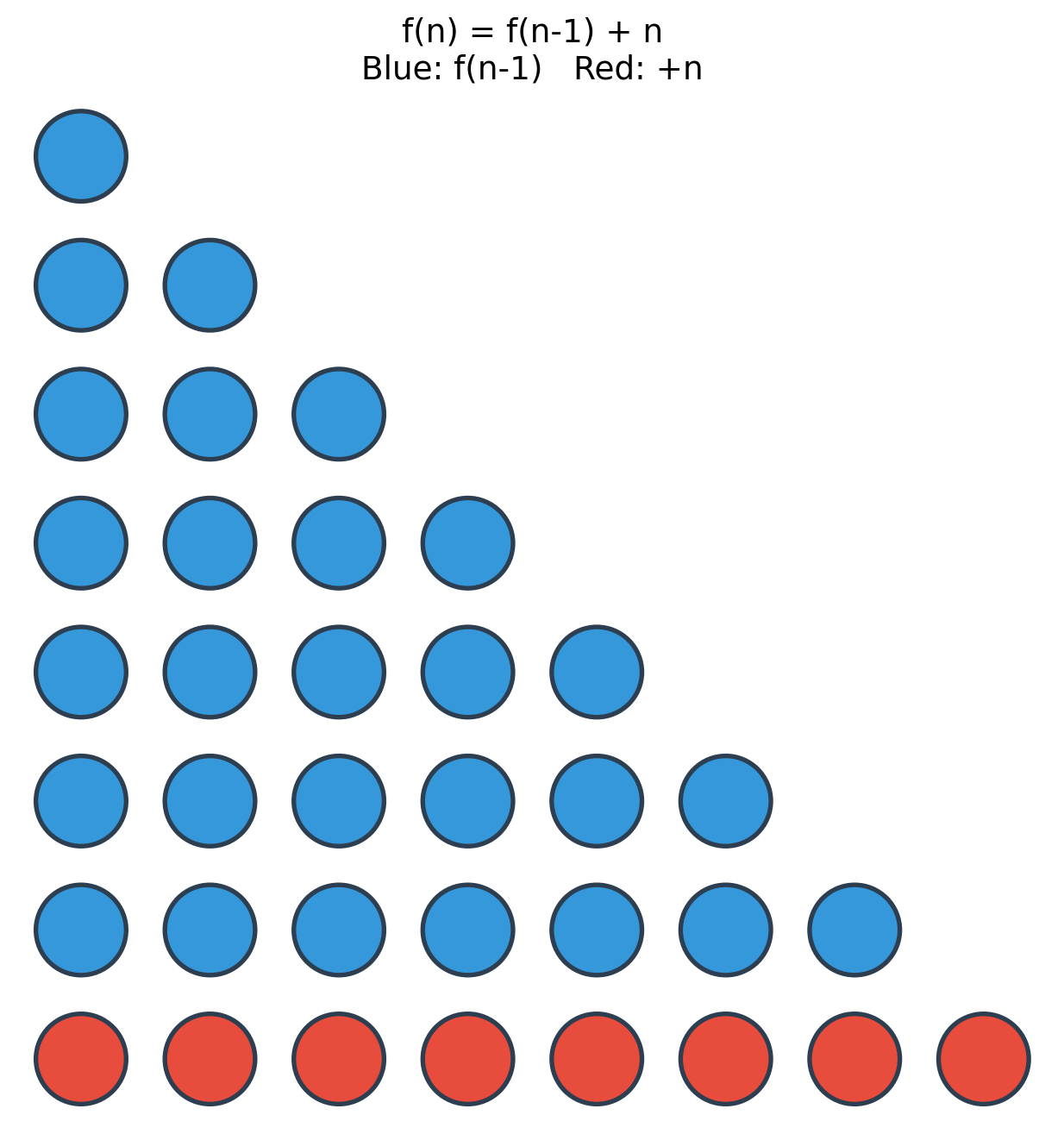

The Recursive Structure: Peel Bottom Row

The Recursive Definition

A recursive mathematical function:

\[f(n) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } n = 0 \\ f(n-1) + n & \text{if } n > 0 \end{cases}\]

Induction = Recursion

| Induction | Math | Recursion |

|---|---|---|

| Consider arbitrary \(n \geq 0\) | \(n\in \mathbb{N}\) | def f(n): |

| Case \(n = 0\): prove directly | \(0\) if \(n=0\) | if n == 0: return 0 |

| Case \(n > 0\): assume \(P(j)\) for \(j < n\) | \(f(n-1)\) defined | Trust f(n-1) works |

| Prove \(P(n)\) using IH | \(f(n-1)+n\) if \(n>0\) | Compute f(n) using f(n-1) |

Same structure. Same reasoning.

The Recursive Code

Consider the math:

\[f(n) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } n = 0 \\ f(n-1) + n & \text{if } n > 0 \end{cases}\]

Intuition for Recursive Design

When you write triangle(n - 1), trust that it works.

This is exactly like relying on the inductive hypothesis in a proof.

Don’t trace through every call. Just ask:

- Does my base case return the right thing?

- If

triangle(n-1)magically gives me the right answer, does my code use it correctly?

The Three Musts of Recursion

For the recursion to work its magic, your code must satisfy:

Handle all valid inputs: Every input needs a case (base or recursive)

Have a base case: At least one case that returns without recursing

Make progress: Each recursive call must get closer to a base case

Same Triangle, Different View

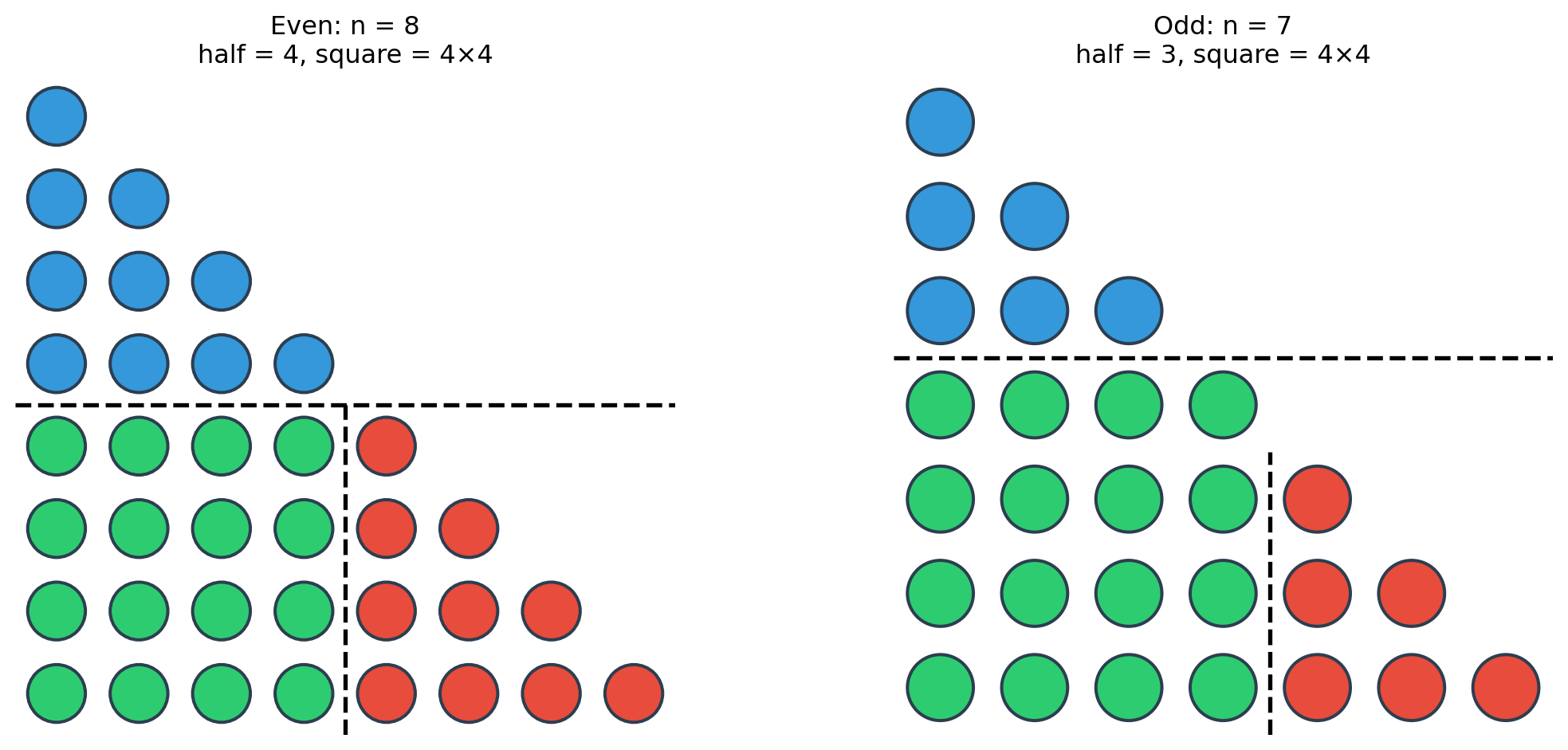

What if we split the triangle differently?

The Quadrant Decomposition

- Blue: Top triangle with \(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor\) rows → \(f(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor)\) dots

- Red: Bottom-right triangle with \(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor\) rows → \(f(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor)\) dots

- Green: Square of size \((n - \lfloor n/2 \rfloor)^2\) dots

\[f(n) = 2 \cdot f(\lfloor n/2 \rfloor) + (n - \lfloor n/2 \rfloor)^2\]

Works for all \(n\).

Two Functions, Same Answer

I forgot to define triangle_fast!

Which is Faster?

Both compute the same answer.

But the recursive structures are different:

triangle(n): callstriangle(n-1)triangle_fast(n): callstriangle_fast(n//2)

Does that matter?

Let’s race them!

The Race

Why So Different?

triangle(n): \(f(n) = f(n-1) + n\)

- Recursion depth: \(n\)

- Total calls: \(n\)

triangle_fast(n): \(f(n) = 2 \cdot f(n/2) + (n/2)^2\)

- Recursion depth: \(\log_2(n)\)

- Total calls: \(\log_2(n)\)

Big Idea: Recursion is About Decomposition

The same problem can have multiple recursive structures.

Different structures lead to different code and different performance.

This is the heart of algorithm design.

What’s Next

- Lab 3: Writing recursive functions

- Week 4: Analyzing recursive running times (recurrences)

- Later: Divide-and-conquer algorithms (merge sort, quicksort)

The triangle race was a preview: smart decomposition → fast algorithms.

Summary

- Recursion: A function defined in terms of itself

- Base case: When to stop

- Recursive case: How to reduce the problem

- Key insight: The same problem can have different recursive structures

- Performance: Structure choice affects speed dramatically