Discrete Math for Data Science

DSCI 220, 2025 W1

December 1, 2025

Announcements

Hashing

Lists vs dictionaries

Suppose we want to store our friends’ favourite drink orders…

Use a list of pairs:

How do we find Bianca’s order?

Finding things with a list

If we store data in a list, to find Bianca’s order we have to search:

- Do you like this?

- What if the list were very long?

- What’s so special about the indices?

Python moment

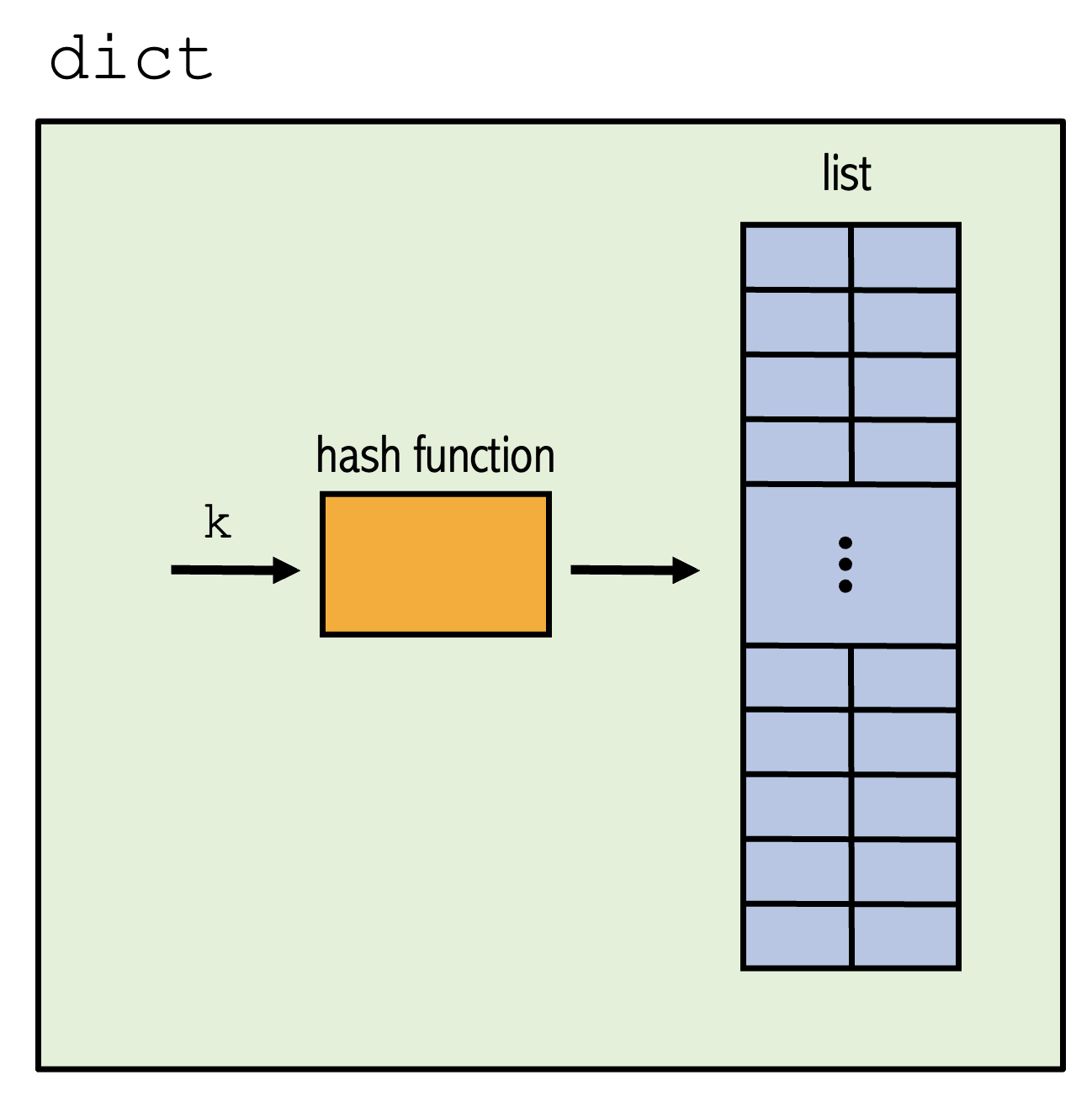

Python has an implementation of an Associative Array called a dict.

Example Key: Value pairs

We often want to map one kind of thing (the key) to another kind of thing (the value):

- Song title → artist

"Anti-Hero" → "Taylor Swift"

- Course code → course title

"DSCI100" → "Intro to DSci"

- Email address → user ID

"alex@ubc.ca" → 1043921

- Date → temperature

"2025-11-27" → 9.3

- Flight → destination

"AC598" → SNA

- City name → population

"Vancouver" → 662248

- Word → number of times it appears

"hashing" → 17

- user ID → Email address

1043921 → "alex@ubc.ca"

All of these are naturally modeled as key–value pairs — exactly what Python dictionaries (and hash tables) are built for.

Hashing

Where we are

- We’ve been thinking about functions:

- \(f : X \to Y\)

- “every \(x \in X\) gets exactly one \(y \in Y\)”

- We saw:

- functions as sets of input–output pairs,

- counting functions,

- huge feature spaces (\(X\) can be enormous).

Today:

- A special and practical kind of function:

- a hash function.

- Goal:

- connect hashing to our function language,

- introduce injective / surjective via a concrete example

Arrays vs associative arrays

A simple array/list:

- Indices: \(0,1,2,\dots,m-1\)

- Values: whatever we store there

- Access: by integer position,

A[3]

An associative array:

- Keys: strings, IDs, course codes,

- Access: by key,

T["DSCI220"]

Idea:

Use a function that turns a key into an index.

That function is called a hash function.

Recall: functions

Formal definition:

A function \(f : X \to Y\) assigns to each input \(x \in X\) exactly one output \(y \in Y\).

- \(X\) = domain

- \(Y\) = codomain

Today’s special case:

- \(X\) = set of keys (e.g., strings like

"DSCI220") - \(Y\) = set of indices \(\{0,1,\dots,m-1\}\)

So a hash function is just:

\[ h : \text{Keys} \to \{0,1,\dots,m-1\}. \]

Example

Let’s start with a set of keys:

"MATH101","DSCI220","STAT201","DSCI221"

And an array:

Goal: Define a hash function \(h\)

Observations

Notes:

- Every key has exactly one hash value. Why must this be true?

- No 2 keys share the same output.

- Every index is the output from some input.

- We call this a perfect hash function

Vocabulary: injective / surjective

Let \(f : X \to Y\).

- \(f\) is Injective (one-to-one) if:

- \(x_1 \ne x_2\) implies \(f(x_1) \ne f(x_2)\).

- No two different inputs share the same output.

- \(f\) is Surjective (onto) if:

- For every \(y \in Y\), there is at least one \(x \in X\) with \(f(x) = y\).

- Every output value is used.

- \(f\) is Bijective if:

- it is both injective and surjective.

- Perfect “pairing” between \(X\) and \(Y\).

On our 4 course codes and 4 buckets, \(h\) is bijective, a perfect hash for that key set.

Perfect hash functions

If we fix a finite set of keys \(K\):

- A function \(h : K \to \{0,\dots,m-1\}\) is a perfect hash for \(K\) if:

- \(h\) is injective on \(K\) (no two keys collide),

- so each key gets its own bucket.

If also \(|K| = m\) and \(h\) is surjective, then \(h\) is bijective on \(K\).

Perfect hash ⇒ no collisions (for that particular key set).

BUT:

- It might be very hand-crafted and fragile.

- It might stop being perfect as soon as we add more keys.

What if we add more keys?

- Keys:

"MATH101","DSCI220","STAT201","DSCI221","DSCI100","CPSC330","STAT200" - Buckets: \(\{0,1,2,3\}\) (4 buckets)

- Hash: \(h(\text{"*}xyz\text{"}) = (x+y+z) \bmod 4\)

Question:

- We now have 7 keys and still 4 bucket. Can any function from these 7 keys to \(\{0,1,2,3\}\) be injective?

- Why or why not?

Pigeonhole principle (PHP)

Formal version in our language:

- If \(|X| > |Y|\), then no function \(f : X \to Y\) can be injective.

Apply to hashing:

- Keys = pigeons

- Buckets = pigeonholes

If we have more keys than buckets:

- \[|\text{Keys}| > m = |\{0,\dots,m-1\}|,\]

- no hash function \(h : \text{Keys} \to \{0,\dots,m-1\}\) can be one-to-one on that key set.

Collisions

A collision happens when two different keys share the same hash value:

\[ k_1 \ne k_2, \quad h(k_1) = h(k_2). \]

By the pigeonhole principle:

- As soon as we have more keys than buckets,

collisions are guaranteed (for every hash function).

A Rosey Hash Function

From “perfect” to “general-purpose”

We’ve seen: On a tiny, fixed set of keys, we can sometimes build a perfect hash

But for general-purpose hashing:

- The key space is HUGE (all possible strings, IDs, …), so we only ever see a sample of keys in our data.

- For any fixed hash function (h : {0,,m-1})…

Collisions before the table is full?

The pigeonhole principle told us:

- If the number of items actually stored in the table is greater than the number of buckets (m),

- then some bucket must contain at least 2 items.

So if we keep inserting more and more items while keeping (m) fixed, collisions are eventually guaranteed.

To ponder for next time:

- When we have fewer than (m) items, will we have collisions?