Lecture 4: -Nearest Neighbours and SVM RBFs¶

UBC 2025-26

If two things are similar, the thought of one will tend to trigger the thought of the other

-- Aristotle

Imports, announcements, and LOs¶

Imports¶

import os

import sys

import IPython

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from IPython.display import HTML

sys.path.append(os.path.join(os.path.abspath(".."), "code"))

import ipywidgets as widgets

import mglearn

from IPython.display import display

from ipywidgets import interact, interactive

from plotting_functions import *

from sklearn.dummy import DummyClassifier

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_validate, train_test_split

from utils import *

%matplotlib inline

pd.set_option("display.max_colwidth", 200)

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

DATA_DIR = "../data/"Learning outcomes¶

By the end of this lesson, you will be able to:

Explain the notion of similarity-based algorithms

Broadly describe how -NNs use distances

Discuss the effect of using a small/large value of the hyperparameter when using the -NN algorithm

Describe the problem of curse of dimensionality

Explain the general idea of SVMs with RBF kernel

Broadly describe the relation of

gammaandChyperparameters of SVMs with the fundamental tradeoff

Quick recap¶

Why do we split the data?

What are the 4 types of data splits we discussed in the last lecture?

What are the benefits of cross-validation?

What is overfitting?

What’s the fundamental trade-off in supervised machine learning?

What is the golden rule of machine learning?

Analogy-based models¶

Suppose you are given the following training examples with corresponding labels and are asked to label a given test example.

An intuitive way to classify the test example is by finding the most “similar” example(s) from the training set and using that label for the test example.

Analogy-based algorithms in practice¶

Herta’s High-tech Facial Recognition

Feature vectors for human faces

-NN to identify which face is on their watch list

Recommendation systems

General idea of -nearest neighbours algorithm¶

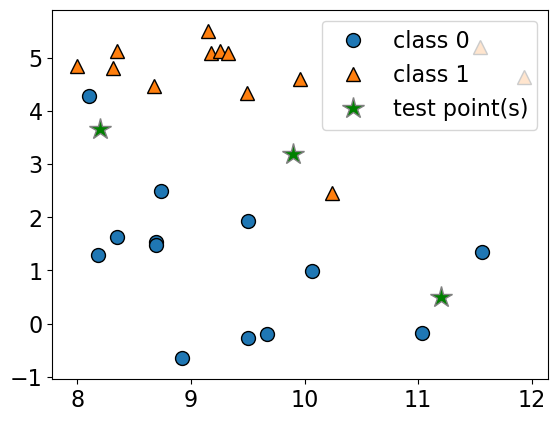

Consider the following toy dataset with two classes.

blue circles class 0

red triangles class 1

green stars test examples

X, y = mglearn.datasets.make_forge()

X_test = np.array([[8.2, 3.66214339], [9.9, 3.2], [11.2, 0.5]])plot_train_test_points(X, y, X_test)

Given a new data point, predict the class of the data point by finding the “closest” data point in the training set, i.e., by finding its “nearest neighbour” or majority vote of nearest neighbours.

import matplotlib

import panel as pn

from panel import widgets

from panel.interact import interact

pn.extension()def f(n_neighbors):

plt.clf()

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4))

plot_knn_clf(X, y, X_test, n_neighbors=n_neighbors)

plt.close()

return pn.pane.Matplotlib(fig, tight=True)

n_neighbors_selector = pn.widgets.IntSlider(

name="n_neighbors", start=1, end=10, value=1

)

# interact(f, n_neighbors=n_neighbors_selector)

interactive_plot = interact(f, n_neighbors=n_neighbors_selector).embed(max_opts=10)

interactive_plotn_neighbors 1

n_neighbors 10

n_neighbors 9

n_neighbors 8

n_neighbors 7

n_neighbors 6

n_neighbors 5

n_neighbors 4

n_neighbors 3

n_neighbors 2

n_neighbors 1

<Figure size 640x480 with 0 Axes>Geometric view of tabular data and dimensions¶

To understand analogy-based algorithms it’s useful to think of data as points in a high dimensional space.

Our

Xrepresents the problem in terms of relevant features () with one dimension for each feature (column).Examples are points in a -dimensional space.

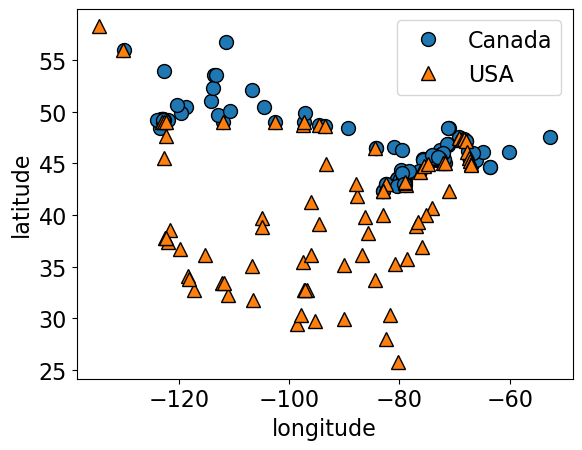

How many dimensions (features) are there in the cities data?

cities_df = pd.read_csv(DATA_DIR + "canada_usa_cities.csv")

X_cities = cities_df[["longitude", "latitude"]]

y_cities = cities_df["country"]mglearn.discrete_scatter(X_cities.iloc[:, 0], X_cities.iloc[:, 1], y_cities)

plt.xlabel("longitude")

plt.ylabel("latitude");

Recall the Spotify Song Attributes dataset from homework 2.

How many dimensions (features) we used in the homework?

spotify_df = pd.read_csv(DATA_DIR + "spotify.csv", index_col=0)

X_spotify = spotify_df.drop(columns=["target", "song_title", "artist"])

print("The number of features in the Spotify dataset: %d" % X_spotify.shape[1])

X_spotify.head()The number of features in the Spotify dataset: 13

Dimensions in ML problems¶

In ML, usually we deal with high dimensional problems where examples are hard to visualize.

is considered low dimensional

is considered medium dimensional

is considered high dimensional

Feature vectors¶

- Feature vector

- is composed of feature values associated with an example.

Some example feature vectors are shown below.

print(

"An example feature vector from the cities dataset: %s"

% (X_cities.iloc[0].to_numpy())

)

print(

"An example feature vector from the Spotify dataset: \n%s"

% (X_spotify.iloc[0].to_numpy())

)An example feature vector from the cities dataset: [-130.0437 55.9773]

An example feature vector from the Spotify dataset:

[ 1.02000e-02 8.33000e-01 2.04600e+05 4.34000e-01 2.19000e-02

2.00000e+00 1.65000e-01 -8.79500e+00 1.00000e+00 4.31000e-01

1.50062e+02 4.00000e+00 2.86000e-01]

Similarity between examples¶

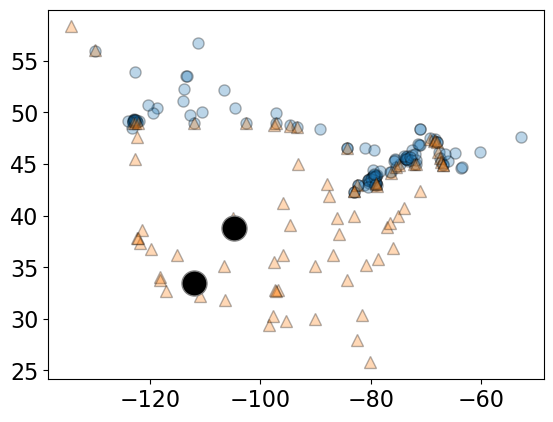

Let’s take 2 points (two feature vectors) from the cities dataset.

two_cities = X_cities.sample(2, random_state=120)

two_citiesThe two sampled points are shown as big black circles.

mglearn.discrete_scatter(

X_cities.iloc[:, 0], X_cities.iloc[:, 1], y_cities, s=8, alpha=0.3

)

mglearn.discrete_scatter(

two_cities.iloc[:, 0], two_cities.iloc[:, 1], markers="o", c="k", s=18

);

Distance between feature vectors¶

For the cities at the two big circles, what is the distance between them?

A common way to calculate the distance between vectors is calculating the Euclidean distance.

The euclidean distance between vectors and is defined as:

Euclidean distance¶

two_citiesSubtract the two cities

Square the difference

Sum them up

Take the square root

# Subtract the two cities

print("Subtract the cities: \n%s\n" % (two_cities.iloc[1] - two_cities.iloc[0]))

# Squared sum of the difference

print(

"Sum of squares: %0.4f" % (np.sum((two_cities.iloc[1] - two_cities.iloc[0]) ** 2))

)

# Take the square root

print(

"Euclidean distance between cities: %0.4f"

% (np.sqrt(np.sum((two_cities.iloc[1] - two_cities.iloc[0]) ** 2)))

)Subtract the cities:

longitude -7.2488

latitude -5.3856

dtype: float64

Sum of squares: 81.5498

Euclidean distance between cities: 9.0305

two_cities# Euclidean distance using sklearn

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import euclidean_distances

euclidean_distances(two_cities)array([[0. , 9.03049217],

[9.03049217, 0. ]])Note: scikit-learn supports a number of other distance metrics.

Finding the nearest neighbour¶

Let’s look at distances from all cities to all other cities

dists = euclidean_distances(X_cities)

np.fill_diagonal(dists, np.inf)

dists.shape(209, 209)pd.DataFrame(dists)Let’s look at the distances between City 0 and some other cities.

print("Feature vector for city 0: \n%s\n" % (X_cities.iloc[0]))

print("Distances from city 0 to the first 5 cities: %s" % (dists[0][:5]))

# We can find the closest city with `np.argmin`:

print(

"The closest city from city 0 is: %d \n\nwith feature vector: \n%s"

% (np.argmin(dists[0]), X_cities.iloc[np.argmin(dists[0])])

)Feature vector for city 0:

longitude -130.0437

latitude 55.9773

Name: 0, dtype: float64

Distances from city 0 to the first 5 cities: [ inf 4.95511263 9.869531 10.10645223 10.44966612]

The closest city from city 0 is: 81

with feature vector:

longitude -129.9912

latitude 55.9383

Name: 81, dtype: float64

Ok, so the closest city to City 0 is City 81.

Question¶

Why did we set the diagonal entries to infinity before finding the closest city?

Finding the distances to a query point¶

We can also find the distances to a new “test” or “query” city:

# Let's find a city that's closest to the a query city

query_point = [[-80, 25]]

dists = euclidean_distances(X_cities, query_point)

dists[0:10]array([[58.85545875],

[63.80062924],

[49.30530902],

[49.01473536],

[48.60495488],

[39.96834506],

[32.92852376],

[29.53520104],

[29.52881619],

[27.84679073]])# The query point is closest to

print(

"The query point %s is closest to the city with index %d and the distance between them is: %0.4f"

% (query_point, np.argmin(dists), dists[np.argmin(dists)])

)The query point [[-80, 25]] is closest to the city with index 72 and the distance between them is: 0.7982

small_cities = cities_df.sample(30, random_state=90)

one_city = small_cities.sample(1, random_state=44)

small_train_df = pd.concat([small_cities, one_city]).drop_duplicates(keep=False)X_small_cities = small_train_df.drop(columns=["country"]).to_numpy()

y_small_cities = small_train_df["country"].to_numpy()

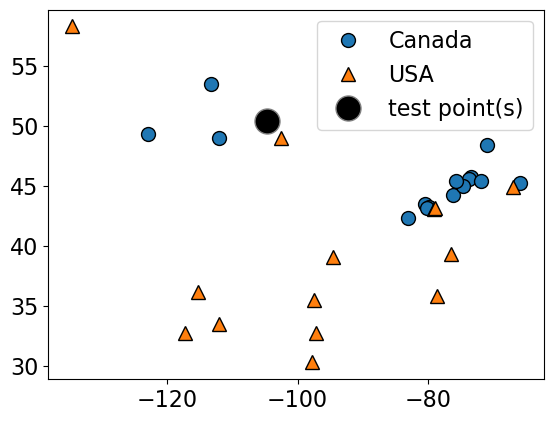

test_point = one_city[["longitude", "latitude"]].to_numpy()plot_train_test_points(

X_small_cities,

y_small_cities,

test_point,

class_names=["Canada", "USA"],

test_format="circle",

)

Given a new data point, predict the class of the data point by finding the “closest” data point in the training set, i.e., by finding its “nearest neighbour” or majority vote of nearest neighbours.

Suppose we want to predict the class of the black point.

An intuitive way to do this is predict the same label as the “closest” point () (1-nearest neighbour)

We would predict a target of USA in this case.

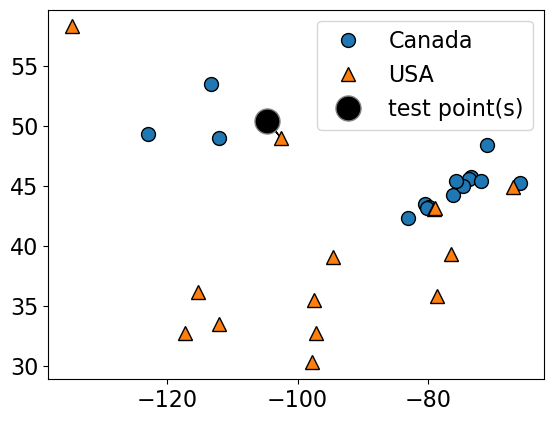

plot_knn_clf(

X_small_cities,

y_small_cities,

test_point,

n_neighbors=1,

class_names=["Canada", "USA"],

test_format="circle",

)n_neighbors 1

How about using to get a more robust estimate?

For example, we could also use the 3 closest points (k = 3) and let them vote on the correct class.

The Canada class would win in this case.

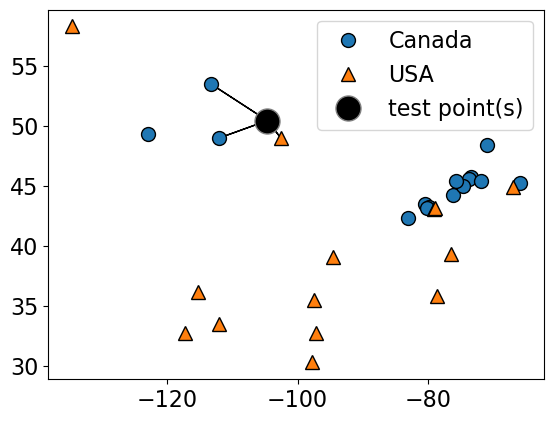

plot_knn_clf(

X_small_cities,

y_small_cities,

test_point,

n_neighbors=3,

class_names=["Canada", "USA"],

test_format="circle",

)n_neighbors 3

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

k_values = [1, 3]

for k in k_values:

neigh = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=k)

neigh.fit(X_small_cities, y_small_cities)

print(

"Prediction of the black dot with %d neighbours: %s"

% (k, neigh.predict(test_point))

)Prediction of the black dot with 1 neighbours: ['USA']

Prediction of the black dot with 3 neighbours: ['Canada']

Choosing n_neighbors¶

The primary hyperparameter of the model is

n_neighbors() which decides how many neighbours should vote during prediction?What happens when we play around with

n_neighbors?Are we more likely to overfit with a low

n_neighborsor a highn_neighbors?Let’s examine the effect of the hyperparameter on our cities data.

X = cities_df.drop(columns=["country"])

y = cities_df["country"]

# split into train and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.1, random_state=123

)k = 1

knn1 = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=k)

scores = cross_validate(knn1, X_train, y_train, return_train_score=True)

pd.DataFrame(scores)k = 100

knn100 = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=k)

scores = cross_validate(knn100, X_train, y_train, return_train_score=True)

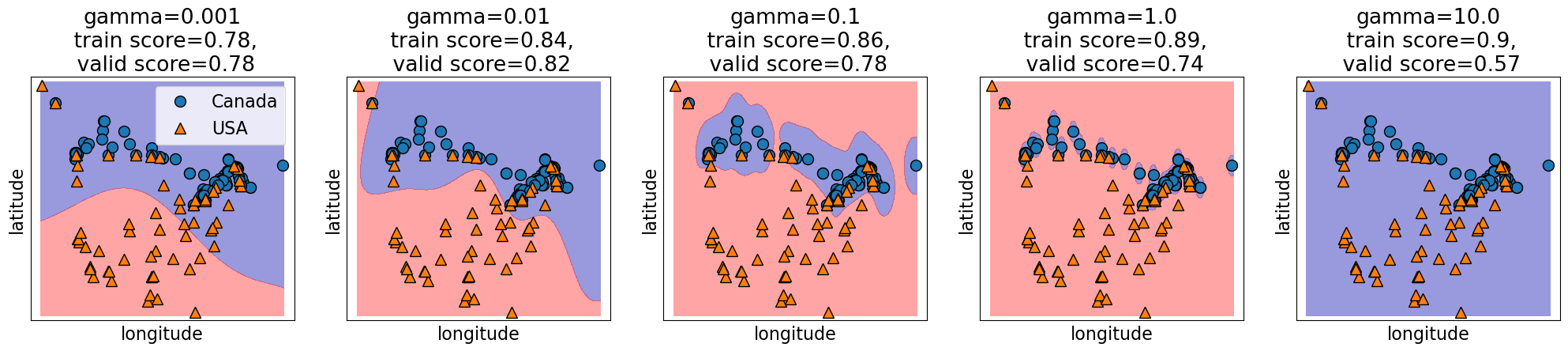

pd.DataFrame(scores)plot_knn_decision_boundaries(X_train, y_train, k_values=[1, 11, 100])

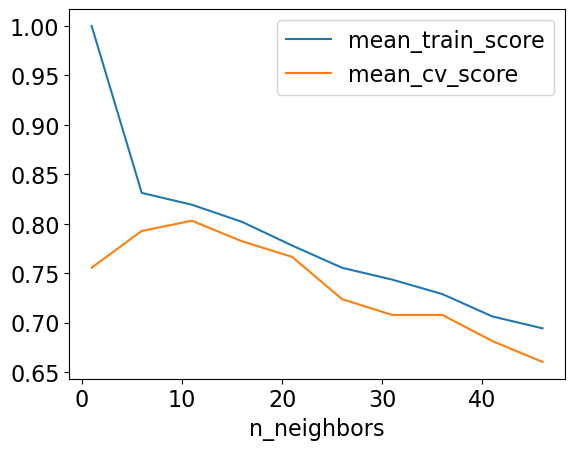

How to choose n_neighbors?¶

n_neighborsis a hyperparameterWe can use hyperparameter optimization to choose

n_neighbors.

results_dict = {

"n_neighbors": [],

"mean_train_score": [],

"mean_cv_score": [],

"std_cv_score": [],

"std_train_score": [],

}

param_grid = {"n_neighbors": np.arange(1, 50, 5)}

for k in param_grid["n_neighbors"]:

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=k)

scores = cross_validate(knn, X_train, y_train, return_train_score=True)

results_dict["n_neighbors"].append(k)

results_dict["mean_cv_score"].append(np.mean(scores["test_score"]))

results_dict["mean_train_score"].append(np.mean(scores["train_score"]))

results_dict["std_cv_score"].append(scores["test_score"].std())

results_dict["std_train_score"].append(scores["train_score"].std())

results_df = pd.DataFrame(results_dict)results_df = results_df.set_index("n_neighbors")

results_dfresults_df[["mean_train_score", "mean_cv_score"]].plot();

best_n_neighbours = results_df.idxmax()["mean_cv_score"]

best_n_neighboursnp.int64(11)Let’s try our best model on test data.

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=best_n_neighbours)

knn.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("Test accuracy: %0.3f" % (knn.score(X_test, y_test)))Test accuracy: 0.905

Seems like we got lucky with the test set here.

❓❓ Questions for you¶

(iClicker) Exercise 4.1¶

Select all of the following statements which are TRUE.

(A) Analogy-based models find examples from the test set that are most similar to the query example we are predicting.

(B) Euclidean distance will always have a non-negative value.

(C) With -NN, setting the hyperparameter to larger values typically reduces training error.

(D) Similar to decision trees, -NNs finds a small set of good features.

(E) In -NN, with , the classification of the closest neighbour to the test example always contributes the most to the prediction.

Break (5 min)¶

Other useful arguments of KNeighborsClassifier¶

weightsWhen predicting label, you can assign higher weight to the examples which are closer to the query example.Exercise for you: Play around with this argument. Do you get a better validation score?

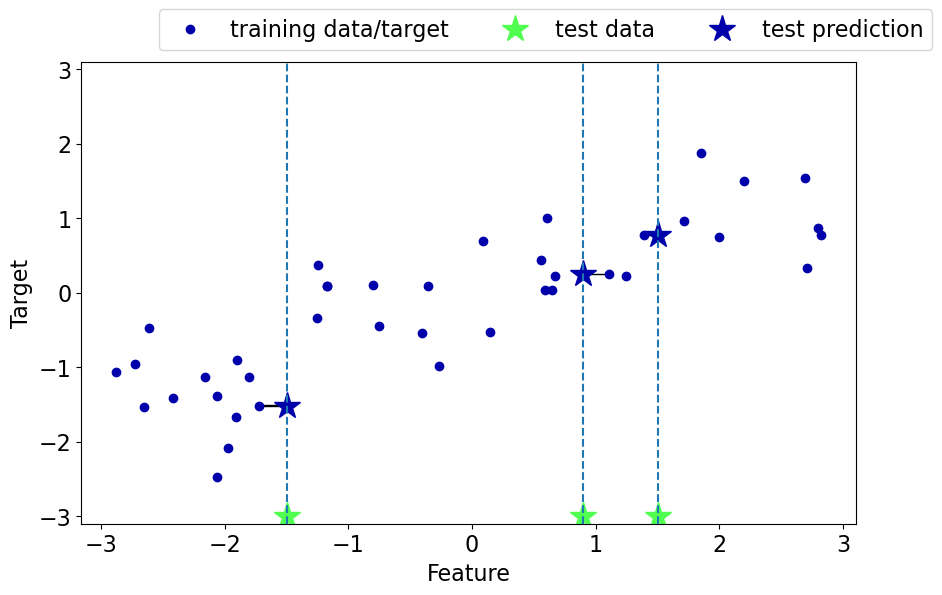

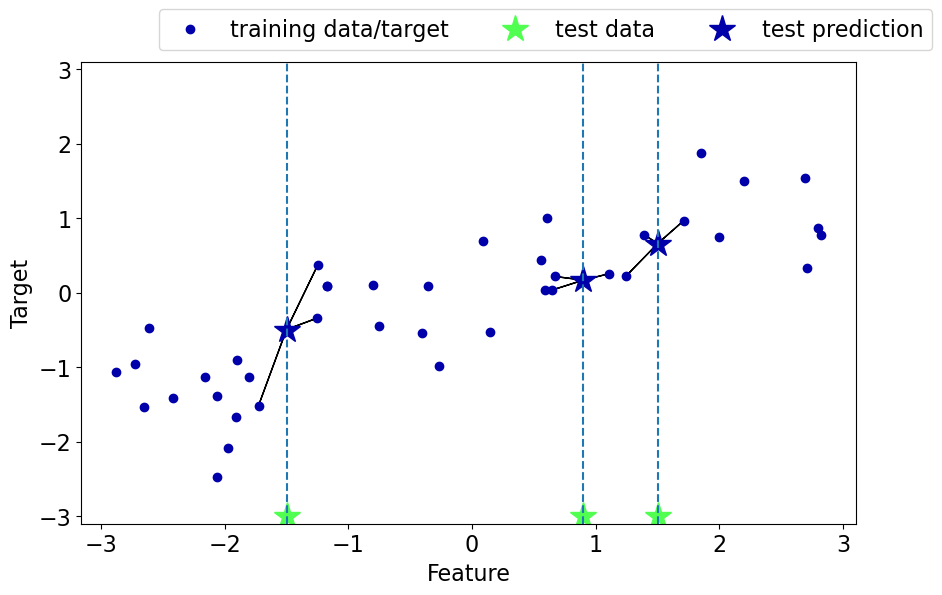

Regression with -nearest neighbours (-NNs)¶

Can we solve regression problems with -nearest neighbours algorithm?

In -NN regression we take the average of the -nearest neighbours.

We can also have weighted regression.

See an example of regression in the lecture notes.

mglearn.plots.plot_knn_regression(n_neighbors=1)

mglearn.plots.plot_knn_regression(n_neighbors=3)

Pros of -NNs for supervised learning¶

Easy to understand, interpret.

Simple hyperparameter (

n_neighbors) controlling the fundamental tradeoff.Can learn very complex functions given enough data.

Lazy learning: Takes no time to

fit

Cons of -NNs for supervised learning¶

Can be potentially be VERY slow during prediction time, especially when the training set is very large.

Often not that great test accuracy compared to the modern approaches.

It does not work well on datasets with many features or where most feature values are 0 most of the time (sparse datasets).

(Optional) Parametric vs non parametric¶

You might see a lot of definitions of these terms.

A simple way to think about this is:

do you need to store at least worth of stuff to make predictions? If so, it’s non-parametric.

Non-parametric example: -NN is a classic example of non-parametric models.

Parametric example: decision stump

If you want to know more about this, find some reading material here, here, and here.

By the way, the terms “parametric” and “non-paramteric” are often used differently by statisticians, see here for more...

Curse of dimensionality¶

Affects all learners but especially bad for nearest-neighbour.

-NN usually works well when the number of dimensions is small but things fall apart quickly as goes up.

If there are many irrelevant attributes, -NN is hopelessly confused because all of them contribute to finding similarity between examples.

With enough irrelevant attributes the accidental similarity swamps out meaningful similarity and -NN is no better than random guessing.

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

nfeats_accuracy = {"nfeats": [], "dummy_valid_accuracy": [], "KNN_valid_accuracy": []}

for n_feats in range(4, 2000, 100):

X, y = make_classification(n_samples=2000, n_features=n_feats, n_classes=2)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=123

)

dummy = DummyClassifier(strategy="most_frequent")

dummy_scores = cross_validate(dummy, X_train, y_train, return_train_score=True)

knn = KNeighborsClassifier()

scores = cross_validate(knn, X_train, y_train, return_train_score=True)

nfeats_accuracy["nfeats"].append(n_feats)

nfeats_accuracy["KNN_valid_accuracy"].append(np.mean(scores["test_score"]))

nfeats_accuracy["dummy_valid_accuracy"].append(np.mean(dummy_scores["test_score"]))pd.DataFrame(nfeats_accuracy)Support Vector Machines (SVMs) with RBF kernel [video]¶

Very high-level overview

Our goals here are

Use

scikit-learn’s SVM model.Broadly explain the notion of support vectors.

Broadly explain the similarities and differences between -NNs and SVM RBFs.

Explain how

Candgammahyperparameters control the fundamental tradeoff.

(Optional) RBF stands for radial basis functions. We won’t go into what it means in this video. Refer to this video if you want to know more.

Overview¶

Another popular similarity-based algorithm is Support Vector Machines with RBF Kernel (SVM RBFs)

Superficially, SVM RBFs are more like weighted -NNs.

The decision boundary is defined by a set of positive and negative examples and their weights together with their similarity measure.

A test example is labeled positive if on average it looks more like positive examples than the negative examples.

The primary difference between -NNs and SVM RBFs is that

Unlike -NNs, SVM RBFs only remember the key examples (support vectors).

SVMs use a different similarity metric which is called a “kernel”. A popular kernel is Radial Basis Functions (RBFs)

They usually perform better than -NNs!

Let’s explore SVM RBFs¶

Let’s try SVMs on the cities dataset.

mglearn.discrete_scatter(X_cities.iloc[:, 0], X_cities.iloc[:, 1], y_cities)

plt.xlabel("longitude")

plt.ylabel("latitude")

plt.legend(loc=1);

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X_cities, y_cities, test_size=0.2, random_state=123

)knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=best_n_neighbours)

scores = cross_validate(knn, X_train, y_train, return_train_score=True)

print("Mean validation score %0.3f" % (np.mean(scores["test_score"])))

pd.DataFrame(scores)Mean validation score 0.803

from sklearn.svm import SVC

svm = SVC(gamma=0.01) # Ignore gamma for now

scores = cross_validate(svm, X_train, y_train, return_train_score=True)

print("Mean validation score %0.3f" % (np.mean(scores["test_score"])))

pd.DataFrame(scores)Mean validation score 0.820

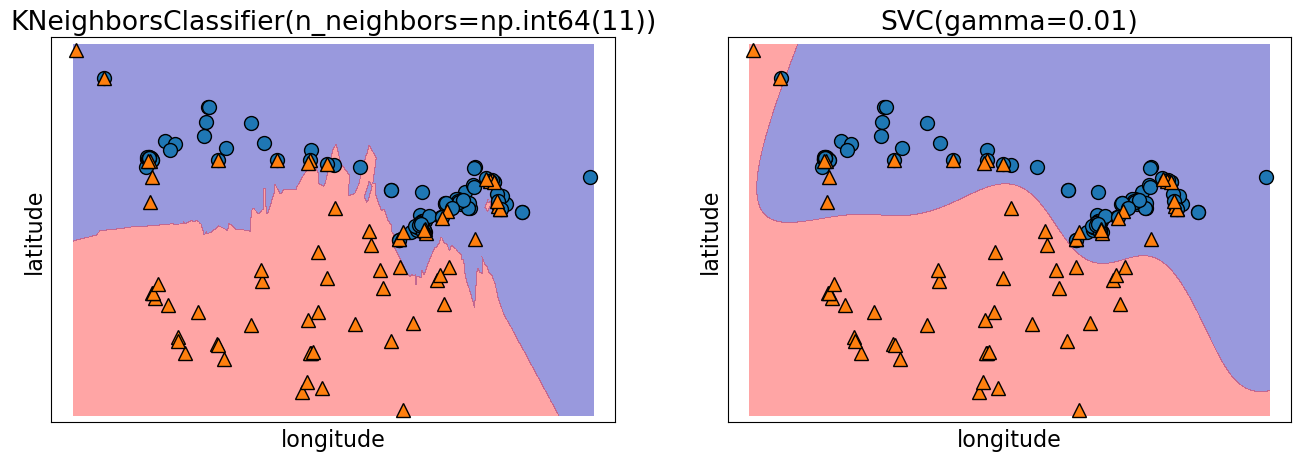

Decision boundary of SVMs¶

We can think of SVM with RBF kernel as “smooth KNN”.

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(16, 5))

for clf, ax in zip([knn, svm], axes):

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

mglearn.plots.plot_2d_separator(

clf, X_train.to_numpy(), fill=True, eps=0.5, ax=ax, alpha=0.4

)

mglearn.discrete_scatter(X_train.iloc[:, 0], X_train.iloc[:, 1], y_train, ax=ax)

ax.set_title(clf)

ax.set_xlabel("longitude")

ax.set_ylabel("latitude")

Support vectors¶

Each training example either is or isn’t a “support vector”.

This gets decided during

fit.

Main insight: the decision boundary only depends on the support vectors.

Let’s look at the support vectors.

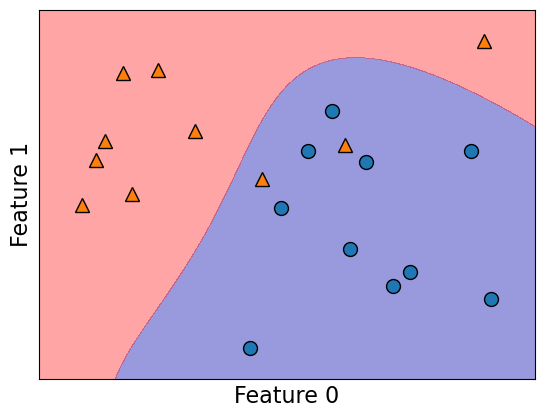

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

n = 20

n_classes = 2

X_toy, y_toy = make_blobs(

n_samples=n, centers=n_classes, random_state=300

) # Let's generate some fake datamglearn.discrete_scatter(X_toy[:, 0], X_toy[:, 1], y_toy)

plt.xlabel("Feature 0")

plt.ylabel("Feature 1")

svm = SVC(kernel="rbf", C=10, gamma=0.1).fit(X_toy, y_toy)

mglearn.plots.plot_2d_separator(svm, X_toy, fill=True, eps=0.5, alpha=0.4)

svm.support_array([ 3, 8, 9, 14, 19, 1, 4, 6, 17], dtype=int32)plot_support_vectors(svm, X_toy, y_toy)

The support vectors are the bigger points in the plot above.

Hyperparameters of SVM¶

Key hyperparameters of

rbfSVM aregammaC

We are not equipped to understand the meaning of these parameters at this point but you are expected to describe their relation to the fundamental tradeoff.

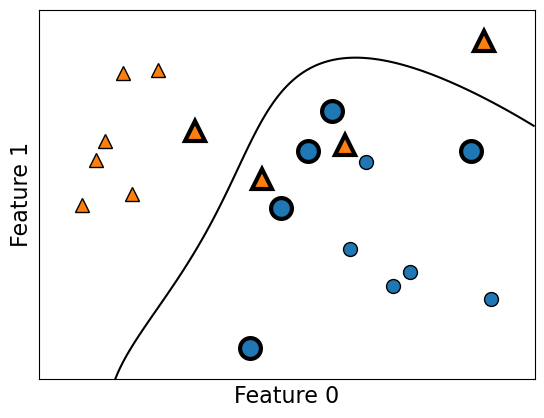

Relation of gamma and the fundamental trade-off¶

gammacontrols the complexity (fundamental trade-off), just like other hyperparameters we’ve seen.larger

gammamore complexsmaller

gammaless complex

gamma = [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0]

plot_svc_gamma(

gamma,

X_train.to_numpy(),

y_train.to_numpy(),

x_label="longitude",

y_label="latitude",

)

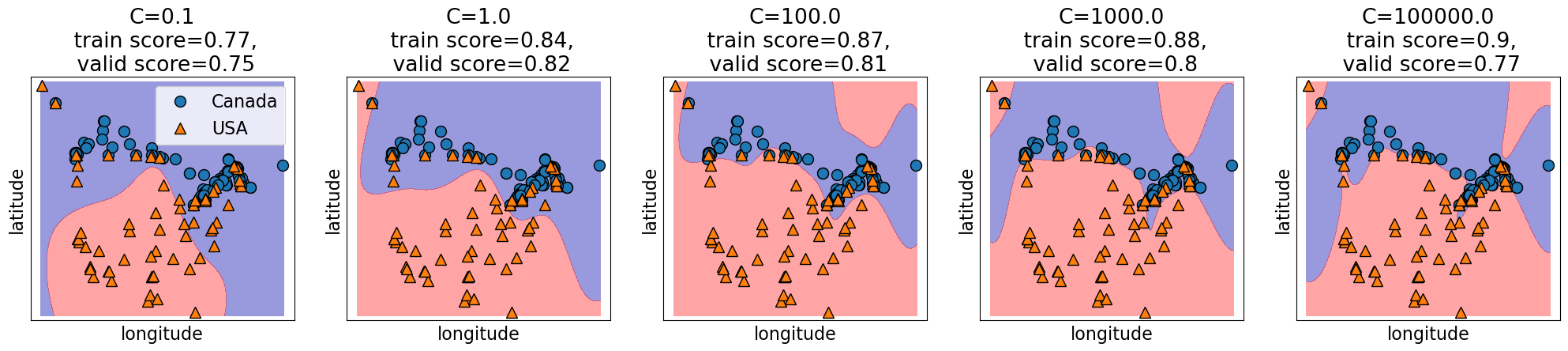

Relation of C and the fundamental trade-off¶

Calso affects the fundamental tradeofflarger

Cmore complexsmaller

Cless complex

C = [0.1, 1.0, 100.0, 1000.0, 100000.0]

plot_svc_C(

C, X_train.to_numpy(), y_train.to_numpy(), x_label="longitude", y_label="latitude"

)

Search over multiple hyperparameters¶

So far you have seen how to carry out search over a hyperparameter

In the above case the best training error is achieved by the most complex model (large

gamma, largeC).Best validation error requires a hyperparameter search to balance the fundamental tradeoff.

In general we can’t search them one at a time.

More on this next week. But if you cannot wait till then, you may look up the following:

SVM Regressor¶

Similar to KNNs, you can use SVMs for regression problems as well.

See

sklearn.svm.SVRfor more details.

❓❓ Questions for you¶

(iClicker) Exercise 4.2¶

Select all of the following statements which are TRUE.

(A) -NN may perform poorly in high-dimensional space (say, d > 1000).

(B) In sklearn’s SVC classifier, large values of gamma tend to result in higher training score but probably lower validation score.

(C) If we increase both gamma and C, we can’t be certain if the model becomes more complex or less complex.

Playground¶

In this interactive playground, you will investigate how various algorithms create decision boundaries to distinguish between Iris flower species using their sepal length and width as features. By adjusting the parameters, you can observe how the decision boundaries change, which can result in either overfitting (where the model fits the training data too closely) or underfitting (where the model is too simplistic).

With k-Nearest Neighbours (-NN), you’ll determine how many neighboring flowers to consult. Should we rely on a single nearest neighbor? Or should we consider a wider group?

With Support Vector Machine (SVM) using the RBF kernel, you’ll tweak the hyperparameters

Candgammato explore the tightrope walk between overly complex boundaries (that might overfit) and overly broad ones (that might underfit).With Decision trees, you’ll observe the effect of

max_depthon the decision boundary.

Observe the process of crafting and refining decision boundaries, one parameter at a time! Be sure to take breaks to reflect on the results you are observing.

from matplotlib.figure import Figure

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.datasets import load_iris

from ipywidgets import interact, FloatLogSlider, IntSlider

import mglearn

# Load dataset and preprocessing

iris = load_iris(as_frame=True)

iris_df = iris.data

iris_df['species'] = iris.target

iris_df = iris_df[iris_df['species'] > 0]

X, y = iris_df[['sepal length (cm)', 'sepal width (cm)']], iris_df['species']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.4, random_state=123)

# Common plot settings

def plot_results(model, X_train, y_train, title, ax):

mglearn.plots.plot_2d_separator(model, X_train.values, fill=True, alpha=0.4, ax=ax);

mglearn.discrete_scatter(

X_train["sepal length (cm)"], X_train["sepal width (cm)"], y_train, s=6, ax=ax

);

ax.set_xlabel("sepal length (cm)", fontsize=12);

ax.set_ylabel("sepal width (cm)", fontsize=12);

train_score = np.round(model.score(X_train.values, y_train), 2)

test_score = np.round(model.score(X_test.values, y_test), 2)

ax.set_title(

f"{title}\n train score = {train_score}\ntest score = {test_score}", fontsize=8

);

pass

# Widgets for SVM, k-NN, and Decision Tree

c_widget = pn.widgets.FloatSlider(

value=1.0, start=1, end=5, step=0.1, name="C (log scale)"

)

gamma_widget = pn.widgets.FloatSlider(

value=1.0, start=-3, end=5, step=0.1, name="Gamma (log scale)"

)

n_neighbors_widget = pn.widgets.IntSlider(

start=1, end=40, step=1, value=5, name="n_neighbors"

)

max_depth_widget = pn.widgets.IntSlider(

start=1, end=20, step=1, value=3, name="max_depth"

)

# The update function to create the plots

def update_plots(c, gamma=1.0, n_neighbors=5, max_depth=3):

c_log = round(10**c, 2) # Transform C to logarithmic scale

gamma_log = round(10**gamma, 2) # Transform Gamma to logarithmic scale

fig = Figure(figsize=(8, 2))

axes = fig.subplots(1, 3)

models = [

SVC(C=c_log, gamma=gamma_log, random_state=42),

KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=n_neighbors),

DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=max_depth, random_state=42),

]

titles = [

f"SVM (C={c_log}, gamma={gamma_log})",

f"k-NN (n_neighbors={n_neighbors})",

f"Decision Tree (max_depth={max_depth})",

]

for model, title, ax in zip(models, titles, axes):

model.fit(X_train.values, y_train)

plot_results(model, X_train, y_train, title, ax);

# print(c, gamma, n_neighbors, max_depth)

return pn.pane.Matplotlib(fig, tight=True);

# Bind the function to the panel widgets

interactive_plot = pn.bind(

update_plots,

c=c_widget.param.value_throttled,

gamma=gamma_widget.param.value_throttled,

n_neighbors=n_neighbors_widget.param.value_throttled,

max_depth=max_depth_widget.param.value_throttled,

)

# Layout the widgets and the plot

dashboard = pn.Column(

pn.Row(c_widget, n_neighbors_widget),

pn.Row(gamma_widget, max_depth_widget),

interactive_plot,

)

# Display the interactive dashboard

dashboardSummary¶

We have KNNs and SVMs as new supervised learning techniques in our toolbox.

These are analogy-based learners and the idea is to assign nearby points the same label.

Unlike decision trees, all features are equally important.

Both can be used for classification or regression (much like the other methods we’ve seen).

Coming up:¶

Lingering questions:

Are we ready to do machine learning on real-world datasets?

What would happen if we use -NNs or SVM RBFs on the spotify dataset from hw2?

What happens if we have missing values in our data?

What do we do if we have features with categories or string values?